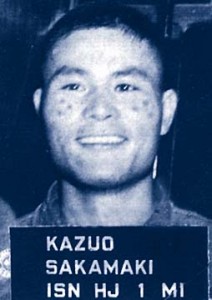

The first POW arriving to Camp McCoy on March 9, 1942 was Ensign Kazua Sakamaki, the first Japanese POW of WWII. He had been the commander of a midget submarine captured off of Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941.[4] Camp McCoy located in Monroe County, WI was one of the first of 130 sites in the United States used to house Japanese, German and Italian POWs during WWII. The 1929 Geneva Convention stipulated prisoner labor must be paid, and camp superintendents quickly realized the benefits of putting POWs to work in America.

Housing POWs in the US

England entered WWII in September 1939 and the United Sates entered in December 1941. By 1942, England was feeling the economic and infrastructure stress of caring for so many German and Italian POWs.[4, p. 15] As England and America moved forward with their war plans to invade North Africa, the burden of caring for more prisoners by England became more profound. It was calculated to be much cheaper to transport the new POWs to America rather than shipping required building materials, food, medical equipment and military guards to England. America reluctantly agreed to take custody of all POWs captured after November 1942 and they would be housed at preexisting military bases in America.[5] It is estimated that by the end of the war there were 371,000 Germans, 51,000 Italians and 5,000 Japanese prisoners in America.[4, p. 16] By the end of the war America was holding more POWs than there had been prewar American Army troops.[4, p.20] Camp McCoy housed 5,000 Germans and 3,500 Japanese and 500 other Asian nationalities.[6]

POW Camp Security

Most of the POW camps in America were located in rural areas. Initially the local governments and citizens were frightened by POW camps being located in their vicinity. The military and citizens were initially afraid of prisoner escapes. As the old Camp McCoy was reconfigured into a POW camp, two eight-foot high cyclone fences were built thirty feet apart around the camp with four strings of barbed wire topping each fence. Additionally, six guard towers with high powered search lights were installed. Tunneling an escape was considered mostly impossible since the soil makeup was mostly sand making any tunneling likely to cave in.

Another security practice was the deployment of a kennel full of fierce, well-trained Canine Corps guard dogs. Also occasionally before each Saturday night camp movie an attack dog demonstration was provided for the prisoner audience with a dog’s handler’s well-padded arm protection getting torn to shreds. One outside movie night a German POW shouted “I’m not afraid of those dogs” a trainer immediately ordered his dog after the POW who climbed the first available tree and hung in the tree until the trainer called the dog off. [1] These dogs with their handlers walked the fence parameters 24×7.

POW Labor

Like all American camps, at Camp McCoy putting prisoners to work meant that they could earn real dollars and camp scrip but most importantly it meant keeping POWs occupied, tired, and out of trouble. During the war America experienced serious labor shortages, especially in rural agricultural communities. Rural areas were especially hard hit by labor shortages since many workers had joined the military while others had moved to urban centers to be employed in war production manufacturing plants that paid much higher wages than farm labor wages. The Geneva Convention stipulated that no prisoner could work more than twelve hours, as well as prisoners must be paid for their labor.

Outside Camp Labor

Wisconsin, like all states during the war suffered from labor shortages. Rural areas around Ft. McCoy in particular were severely affected. Most of the outside POW labor in Wisconsin and at Camp McCoy had to do with agriculture. Tasks included picking corn, other vegetables and fruits and working inside packing plants. In other parts of Wisconsin, POWs worked bailing hemp, working in tanneries, dairies, lumber mills and nurseries. Most camp POWs however remained within the camp as laborers. The few that did have outside jobs either marched to the job site or were transported in Army trucks.

Outside camp guards carried side arms and sometimes rifles. Outside camp work details usually numbered 102 prisoners, four guards and two watch dogs.[4, p. 24] Outside camp labor security was variable depending upon the guard detail and as the war neared the end, security became very lax. Some canning factory guards would drop off prisoners and then leave them to work the shift and return at the shift end to transport the prisoners back to camp. A guard at the Dairyland Cooperative in Hartford regularly set his rifle down and took a nap. Prisoners would wake him when an officer was arriving.[4, p. 25] At some Wisconsin camps outside work crew guards actually took prisoners to nearby cafes for lunch![4, p. 25] The threat of escape and attempts was very low.

Inside Camp Labor

Within Ft. McCoy prisoners did kitchen patrol duty, such as cooking and kitchen cleaning. They also provided camp maintenance, motor pool maintenance and repair labor, constructed camp buildings, worked as barbers, welders and medical technicians. As additional prisoners filled the camp, German prisoners built additional bunk houses, latrines and waste disposal incinerators.

In general the Japanese did very little inside or outside labor, believing such work was aiding the enemy. Germans however had no such problem and were caring for base operations. “By November of 1945 some of the German POWs at McCoy had the run of the place,” recalled a guard Arthur Hotvedt.[2]

Can’t We Be Friends? NO!

Since Camp McCoy had many different prisoner nationalities, barbed wire fences separated barracks by nationality. Still things would often get dicey as different nationalities mixed together each evening on common areas such as the canteen, PX and barber shops. While Germany and Japan were allies with The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, within the camp they were very hostile to each other and each group believed in their own racial superiority and would trade insults towards each other. Commander Lt. Colonel H. I. Rogers told Colliers Magazine, “but for each race, the other is nonexistent. They hate each other.”[3]

As the war continued within the Japanese camp area, animosity also arose between the navy and army prisoners. Army prisoners blamed Japan’s military failures on the navy as the American military hoped island by island closer to Japan. The Japanese army prisoners had a more warrior class enthusiasm for the war than the captured navy prisoners. As the Japanese navy sustained more naval defeats the number of navy POWs in the camp exploded in comparison to the army prisoners. As the navy had many more prisoner officers than the army, they commanded the camp prisoners. This did not sit well with gung ho army prisoners and they refused to take orders from any naval officers.

Camp Life

According to the Geneva Convention POWs had to be served the same food as that of their guards. In 1943 it was approved to serve prisoners their own ethnic foods. Which was happily received by all prisoners.

The Japanese diet included dried fish, meats, rice pickles, soy sauce and many vegetables, while German menus included smoked meats, pig knuckles and various sausages.[4, p. 28] Church services were made available to all prisoners including Buddhist celebrations, held at a shrine built by the Japanese along with supplies of incense sticks.[4, p. 29] The same medical and dental care was provided to prisoners and guards alike. Red Cross mail and packages could be both received and sent home. Script that was earned could be used for toiletries, razors, socks, candy, gum, sodas, tobacco and sometimes beer.[4, p. 29]

Some prisoners even took college correspondence classes. A few German prisoners even earned college credits from the University of Wisconsin-Madison[4, p. 30] while 40 percent of the Japanese prisoners earned either high school or college credits.[4, p. 30]

Townspeople came to see little difference between the POWs and themselves. In Wisconsin many civilians where first or second generation Germans and would spend time conversing in German to the POWs. In fact, during the mid-forties, one third of the state’s population was of German ancestry.[4, p. 33] Many of the state’s German population had escaped the Kaiser’s pre-WWI conscription. Occasionally through this interaction they would discover they had the same relatives in Germany.

Repatriation

The survival rate of prisoners held in America was unprecedented in the history of war. Of the total number of 450,000 POWs held in America only 477 died with natural causes being by far the leading cause of death.[7] Still with the signing of each peace treaty, it took longer than expected to send prisoners home. At the end of 1945 only 75,000 out of 450,000 had been repatriated.[4, p. 44] By the end of June 1946 all prisoners had been sent home except those serving sentences in American jails.[4, p. 44]

Primary Sources

- Robert Gard, Camp McCoy PW guard, interviewed in Appleton, WI by Crowley Betty, 24 November 2000, cited in [4, p. 16].

- Sgt. Arthur Hotvedt, Ft. McCoy guard 1945 to 1946, interviewed in Eau Claire, WI by Betty Cowley, 6 November 2000, cited in [4, p. 15].

- Devore, Robert. 1944. “Our Pampered’ War Prisoners,” Colliers, 14 October, p. 57 [4, p. 15].

Secondary Sources

- Crowley, Betty. Stalag Wisconsin: Inside WW II prisoner-of-war camps (Milwaukee: Badger Books, 2002).

- “About This Item.” The Untold Story of Camp McCoy: Japanese Prisoners of War in the Heart of Wisconsin During the Second World War. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

- Robin, Ron. The Barbed-Wire College: Reeducating German POWs in the United States During World War II. Princeton UP, 1995.

- Krammer, Arnold. NaziPrisoners of War in America. New York: Stein and Day, 1979.