The Soo Locks played a critical role during World War II as the passageway through which 90% of the nation’s iron ore was shipped. As the war escalated paranoia grew that the Locks would be targeted by German saboteurs or long range bombers. To deal with this potential threat, military presence in Sault Sainte Marie grew considerably throughout the war.

Overview

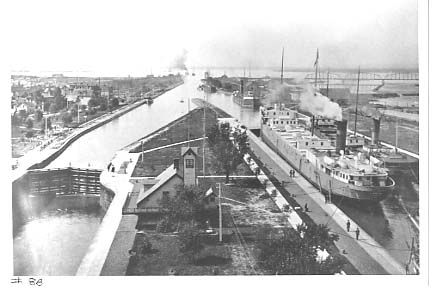

The Soo Locks are a major shipping channel located in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan; connecting Lake Superior to Lake Huron through the St. Marys River. They were constructed as a way to deal with the roughly 21ft drop between the two bodies of water. During the 1940s the Soo Locks were one of the busiest shipping channels in the world: through its gates, 90% of the nation’s iron ore (over 300 million tons between 1941-1943!) was transported to the steel mills and factories in Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania, which would become vital to the allied war effort [5][7][8]. It was crucial during the years leading up to and during the war that the locks not sustain any damage as the steel mills down route of the locks operated with minimal material reserves and would be crippled very quickly if deliveries of ore were to cease [4][7][8].

As the war escalated and America’s involvement increased there was concern over the potential for a homeland attack targeting the Soo Locks. In response to these fears the garrison at Fort Brady on the American side was increased from about 600 in 1938 to a peak of almost 12,000 during the war. Defensive preparations at the Locks started as early as 1939, when after Hitler’s invasion of Poland, the US coast guard began patrolling the downstream portions of the locks [7][8]. In 1941, still 9 months before the US entry into the war, Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the military district of Sault Marie giving command of the district to Colonel Fred Cruse and replacing the 2nd infantry at Ft. Brady with the 702nd Military Police Battalion. In 1940, 200 ski and snowshoe troops were deployed to the fort and by 1942 members of the 131st Infantry and 100th Coastal Artillery were being stationed at the locks [2][7][8][9]. The final wave of defensive installments came later that year when the 399th Barrage Balloon Battalion arrived [6][7][8].

The defensive strategy for the locks was extremely comprehensive, defending from land, air and sea. The troops garrisoned at Fort Brady throughout the war were responsible for patrolling the land around the Soo, working guard duty shifts at the Locks, and manning the spotlights and anti aircraft gun emplacements spread throughout the town [3][7][8]. Passive defensive measures were also employed by setting up heavy steel cables affixed to 30-ft barrage balloons to deter dive bombers, and steel mesh netting was installed up and downstream from the locks to intercept torpedoes. Infrastructure was even developed on Sugar island to house more significant gun emplacements outside of Sault Sainte Marie proper [7][8].

All in all, the militarization of Sault Sainte Marie took a toll on the community throughout the war. Food, housing, and sanitation resources were all stretched thin by the massive population influx in the community and civilians felt the burden of troops setting up artillery and anti-aircraft guns in their yards, staying in their homes, and setting up camps in what were previously public parks [3][7][8]. Despite these hardships, spirits stayed high in the Soo throughout the war and by 1943 military presence around the Locks began to scale back dropping down to first 7,000 and then 2,500 later that year. By 1944 Fort Brady is reclassified to a surplus fort and only 600 soldiers remained stationed there, defensive measures around the Locks cease, and the Soo is left with only with the brief memory of what it was like to live in the warzone that wasn’t [6][7][8]. Years after the war ended locals still reminisce about the soldiers they met, and the antics that went with living with a military population during the war. Overall there is a positive connotation to the occupation despite the inconvenience caused by the military presence during these years [7].

Interview with George DeBaar

In a 2008 interview with Grand Valley State University, George DeBarr recalled some of his experiences stationed at the Soo during the war. George DeBarr was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan in April 1923. He grew up in a lower-middle class family and dropped out of school at a young age to help support his family during the Great Depression. In December Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese and, upon the declaration of war many of George’s friends enlisted in the army. George opted out until he was drafted in January of 1943 [1].

George was inducted into the army on the 15th of January, and recalls the extreme secrecy of the army during these early years. He was given a winter coat and loaded onto a freight train to be shipped off without even being given a destination. Upon reaching Mackinac Straits he crossed with his compatriots via ferry and then was trucked to Fort Brady. When he arrived at the fort George’s first memory was how cold it was there, he describes it as “real winter… unlike what they had downstate” [1]. From January to August 1943 George was stationed at Fort Brady with the 131st Infantry in Company F. While here, he completed basic training and was involved in infantry patrols in the area surrounding the Locks. Company F was also the designated trucking company for the base, as such George was involved in this as well [1].

From what he remembers, George does not recall very many disciplinary issues with 131st while stationed at the Soo, as he says “the drill sergeants were stern, but fair and respected” and “most men adjusted to the military well…but there was an incident where some men held up a movie theater shortly before being deployed” [1]. The other major aspect George recalls from his time at Brady was the extreme standards to which the troops were held. It was emphasized around the base that they would be a “showcase” to the rest of the world and were required to keep their arms and barracks in pristine shape. In August the 131st shipped out to New York and that September crossed the Atlantic to Britain in preparation for D-Day [1].

Civilian-Military Relations at the Soo

Prior to WWII Fort Brady only housed four companies, a fraction of what the base’s size would grow to during the war. Although the base was only ever commissioned for 7,500 troops, at its peak there were almost 12,000 people, (almost double the population of the Soo at the time!), stationed at Fort Brady stretching the fort well past its capacity. As such many soldiers had to find housing arrangements in gymnasiums, churches, and even private homes. The civilian hospitality to the troops in these early years of the buildup is well documented, as the community offered not only shelter, but fresh produce, clothing, and various other services to the young men stationed there. Throughout the course of the war emergency air raid drills were held frequently for both the soldiers and civilians. Civilians from Sault Sainte Marie got involved in military affairs through contract work constructing barracks, building officer barracks, and gymnasiums and tennis courts on the base, in addition many residents of the Soo would get involved in the civilian air defense corps which had upwards of 1,000 volunteers at its peak and operated binoculars and spotlights to search for enemy aircraft 24-hours a day [7][8][9].

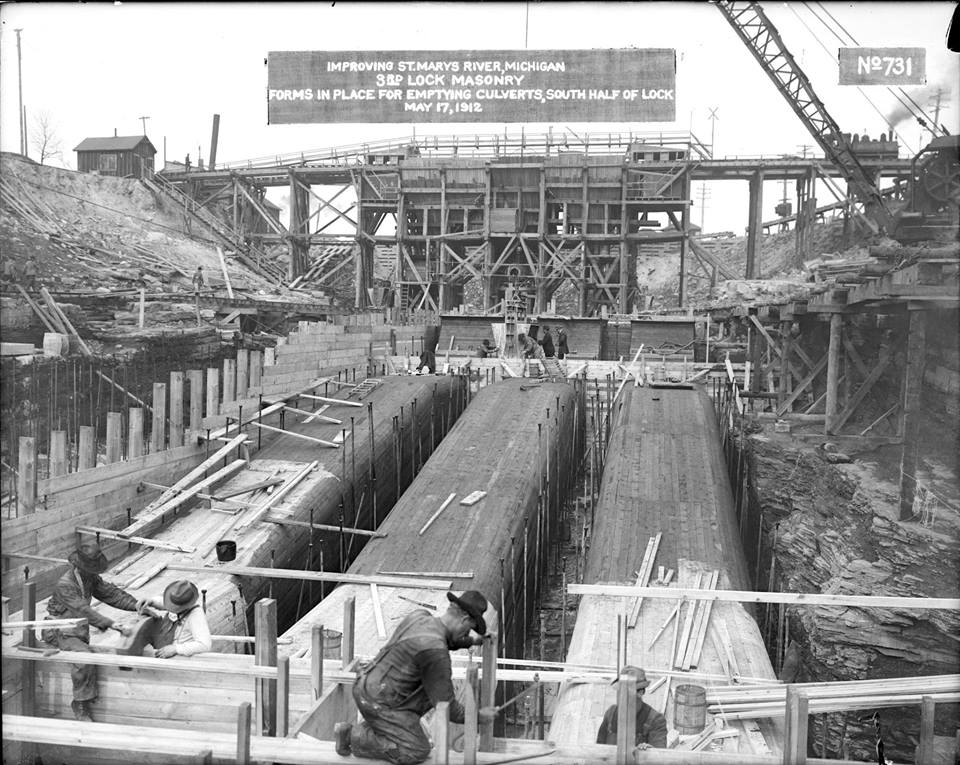

Activities at Fort Brady ran year round and soldiers were constantly training, on guard duty, or getting involved in recreational activities. During the war soldier led construction projects were undertaken on base constructing tennis courts, broomball rinks, and various other quality-of-life improvements. Special winter training was also conducted, making use of the extreme weather conditions in the UP. Troops would frequently train at below zero temperatures to prepare themselves for the worst case scenarios of winter fighting in Europe [9]. In May 1942 work began on the Douglas MacArthur locks, an expansion project prompted by the collapse of a railway bridge upstream. This even sent the military community into a panic as it backed up the locks for several days. Shortly afterwards a bill was rushed through congress to approve the replacement of the Weitzel Lock. Construction was be overseen by the Army Corp of Engineers and the project took only 14 months, an unprecedented speed for such a feat [7][8].

Despite all this though, the military presence in the Soo was not entirely positive. Following the military buildup during WWII public access to the locks was forever changed, the park around the locks remains a military installment and restricts civilians from getting too close to the ships. Additionally some townies resented the loss of so much of their public space due to the influx of population; town parks, gyms and even privately owned land was even encroached on with anti-aircraft installments being placed in many familie’s yards [3][7][8]. Other inconveniences came from the rowdiness of the soldiers who would occasionally get drunk and cause issues at local bars and restaurants and sometimes would get involved in more serious crime. Military accidents also disrupted life in the town, on more than one occasion barrage blimps would break free and crash into town or occasionally float far away and into other Michigan communities [7][8].

Despite all of this though by the time the war ended civilian morale was high, and tourism from the soldiers stationed there was a boon to the local economy for years to come. After Fort Brady was decommissioned it was taken over by Michigan Technological University and established as a satellite campus for military engineering curriculum, which attracted many soldiers who were stationed there during the war to pursue their degrees [6][7][8][9]. Even today stories circulate through the Soo of residents who have ran into soldiers stationed there years later and the hospitality of the community getting paid back by the men who were treated so well by them while they were stationed at the Locks. Today Engineers Day is held at the locks once per year where visitors and tourists can get a up close look at the inner workings of the locks and get a glimpse of what it would have been like before the WWII buildup forever fortified the land surrounding the installment [7][8].

Final Thoughts

Over the course of less than three years the Soo Locks saw massive military buildup followed by rapid disarmament. During these few stressful years paranoia ran rampant and tensions were high, but in the face of adversity the people of Sault Sainte Marie welcomed soldiers with open arms and did what they could to accommodate them in the hostile environment of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The scale and speed of the buildup highlights not only the logistical prowess of the United States military during the Second World War, but also the unbelievable importance the Soo Locks played during the conflict. With upwards of 12,000 troops stationed at Fort Brady and every feasible avenue of attack guarded against, this valuable military asset was in good hands throughout the war. Although the closest the axis ever got to threatening the Locks were unmanned bomb balloons sent from Japan, there is no question that the diligence of the soldiers and community at the Soo was valuable and that their work during the war would leave a lasting legacy. For more information about the logistical importance of the locks during the war check out Ben Pletcher’s article Soo Locks: The Jugular Vein of the US WWII War Production Effort, for more information about Fort Brady after the war see Tom Spicuzza’s article Michigan College of Mining and Technology, Sault Ste. Marie Branch.

Sources

[1] DeBaar, George. “Veterans History Project.” Interview by James Smither. Special Collections & University Archives. Grand Valley State University, 14 Aug. 2008

[2] “Army Tightens Control of Soo Locks Defenses”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 24 March, 1943. p. 8.

[3] “Secrecy Lifted On Hidden Guns At Soo Canal”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 17 August, 1945. p. 15.

[4] “WPB Tells How Vital Industry Was Guarded”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 16 September, 1945. p. 12.

[5] Joachim, J. George (1994). Iron Fleet: The Great Lakes in World War II.

[6] June, M. Mary (2002). Timeline History of Sault Ste Marie. Web. <saultcity.com>

[7] North, Rachel (2014). Northern Michigan History: When the Soo Locks Readied for World War II. Web. <mynorth.com>

[8] Stevens, Deidre (2012). When World War II Came to the Sault. Historical Society of Michigan. Web. <hsmichigan.org>

[9] “World War II At Fort Brady.” From Fort to Future. Lake Superior State University, 2000. Web. <lssu.edu>.

Further Reading:

- Wikipedia: The Soo Locks

- Wikipedia: Fort Brady