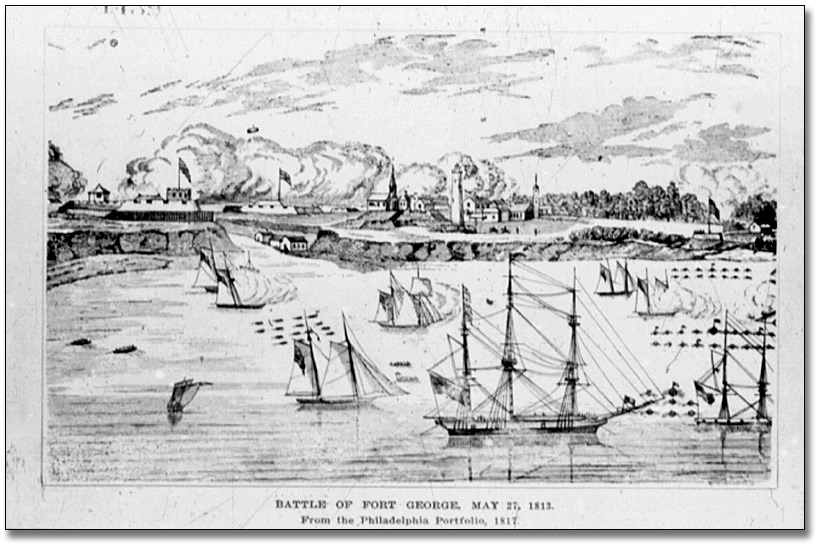

On May 27, 1813, American forces led by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, Colonel Winfield Scott and Major General Henry Dearborn, launched an amphibious assault on Fort George, commanded by British Brigadier-General John Vincent. Launched from Fort Niagara on the opposite side of the Niagara River, the Americans aimed to drive the British and Canadian forces out of the Niagara frontier and gain control of the northern Niagara River. Following a victory in York (present-day Toronto) on April 27, a council of war unanimously decided in favor of an attack on Fort George (Cruikshank, 1904, p24).

Before The Battle

Fort Niagara, located on the American side of the Niagara River in the state of New York, was previously under British occupation until 1794 when Jay’s Treaty was signed by the United States and Great Britain, which resolved issues lingering since the Treaty of Paris (1783, ended the American Revolution). This treaty mandated the withdrawal of British Army units from forts in the Northwest Territory. Fort George was subsequently built across the river in the Canadian province of Ontario.

In the months leading up to the battle, the two forts traded bombardment from their guns. Fort George and its guns were heavily damaged as a result of these volleys (Cruikshank, 1904, p16). Vincent knew that an attack from the Americans was imminent, and positioned his forces mostly along the Niagara River, “assuming the American attack would come from that direction” (Hurley, 2012).

The Battle (American Perspective)

Due to a westward wind, Commodore Isaac Chauncey arrived in the Niagara area on May 25 after departing from Sackett’s Harbor on the 22nd. An immediate meeting with General Dearborn was held to make arrangements for an attack against Fort George. It was agreed upon to attack as soon as the weather allowed for a safe amphibious landing. By the evening of the 26th, the weather had moderated and the attack was planned for the following morning. The troops boarded the vessels between 3:00 and 4:00 a.m., and approached the shoreline near Fort George in calm waters under the cover of fog (Palmer, 1814, p224-225).

On the morning of May 27, 1813, as the early morning fog dispersed, sixteen vessels of different sizes were seen across the mouth of the river accompanied by no less than 134 boats and scows (Cruikshank, 1904, p27). The assault began at about 9 o’clock when “the guns of Commodore Perry’s schooners opened fire on the British batteries and covered the American landing commanded by Colonel Winfield Scott” (Hurley, 2012). The landing occurred to the west of the mouth of the Niagara River, contrary to Gen. Vincent’s expectations. Vincent reported that “the fire from the shipping so completely enfiladed and scoured the plains, that it became impossible to approach the beach” (Montross, 1958, p41). The Americans were able to land with no resistance under the cover of artillery fire, but their first attempt to ascend up the banks was thwarted by the musketry of the opposition, which had been concealed by a ravine (Palmer, 1814, p225). They were finally able to push up the banks and form a line on the plain, where for “fifteen minutes the lines exchanged a rapid and destructive fire, at a distance of only six or ten yards” (Cruikshank, 1904, p29). It was later reported that “nearly 400 of both armies lay stretched on a plot of ground not more than 200 yards in length and 15 in breadth” (Cruikshank, 1904, p34).

By ten o’clock the Americans had succeeded in landing the greater part of their field artillery, and began advancing on Fort George. A strong east wind sprung up and became so strong that it made landing additional troops dangerous, causing Commodore Chauncey to order the remaining ships into the river (Palmer, 1814, p226). The American troops had not brought horses to haul their guns, so their land advance was slow (Cruikshank, 1904, p30). The fort became the victim of constant artillery fire, and with the landing of additional American troops Vincent realized that he was outnumbered and outgunned. At noon he ordered the guns to be spiked, the magazines destroyed, and the fort to be evacuated (Hurley, 2012).

The retreat towards Queenstown was quickly and quietly executed and almost went unnoticed by the American forces. They approached the fort with extreme caution due to the constant sounds of explosions within, and Colonel Scott was in fact unhorsed when struck by a large splinter that broke his collarbone (Cruikshank, 1904, p32). Upon entering the fort they found it mostly empty, save for a few soldiers still in the process of dismantling the fort (Cruikshank, 1904, p32). General Dearborn wrote to the Secretary of War from Fort George, “We are now in possession of Fort George and its immediate dependencies. We had 17 killed and 45 wounded. The enemy had 60 killed and 160 wounded. We have taken 100 prisoners exclusive of the wounded.” (Cruikshank, 1902, p247).

The Americans were unsuccessful in cutting off the British retreat to the south along Portage Road, and Scott was ordered to halt his retreat and return to Fort George for fear of being led into a British ambush (Hurley, 2012).

The Battle (British Perspective)

Prior to the 27th of May, the British Colonel Myers began to notice demonstrations of the enemy for a serious attack. On the morning of May 27th, Captain Merritt and Colonel Harvey noticed the enemies advancing fleets while on a nocturnal ride (Cruikshank, 1902, p261). The morning was calm and very foggy, but at intervals the enemy’s fleet could be seen, amounting to at least 134 boats and sixteen vessels (Cruikshank, 1902, p257). General Vincent thought that the enemy would land a part of their force up the river and conduct a joint attack on the fort, but he was mistaken (Cruikshank, 1902, p261). By 6:00 a.m. it became clear that the major landing effort would take place near Two Mile Creek to the west of Fort George, with the Madison having occupied a location near it. Under the enemies fire, a large part of it large caliber, the British forces were only able to form in ravines (Cruikshank, 1902, p257).

The enemy landed on shore near Two Mile Creek with very great force. During the first attack by the British, under heavy fire from the American vessels, Colonel Myers was wounded and was forced to retire from the battle. Due to the fire from the vessels, the battle soon became unequal and the British forces began to attack and retreat on multiple occasions (Cruikshank, 1902, p258). As there were no more ravines to cover the retreat from the tremendous fire from Fort Niagara and the vessels, coupled with the enemy landing a number of field artillery, the British troops unwillingly resorted to a retreat to the Council House at around 10:00 a.m.

The hope that was the American forces would approach across the plain in front of them, but they soon realized that the riflemen were entering the bush on their left flank towards their rear. It was then that a retreat towards Queenstown was necessary, and the troops inside the fort were ordered to first blow up the ammunition and burn the government stores of provision (Cruikshank, 1902, p258). The retreat was conducted with order, and the American forces were too exhausted to pursue.

Captain Fowler wrote to Colonel Baynes on May 29th from Forty Mile Creek, reporting that the enemy landed no less than 8,000 men on the day of the battle, with 5,000 in the first instance and 3,000 more throughout the day (Cruikshank, 1902, p259).

After The Battle

General Vincent arrived in Burlington Heights on June 2nd with eleven field guns and 1800 seasoned soldiers, who were in high spirits despite recent events and eager to meet the enemy again on more equal terms. This was displayed three days later in their success at Stoney Creek (Cruikshank, 1904, p34).

The Americans, however, were disappointed in the incompleteness of their success. They marched for Queenston on the 28th but seemed to have lost all track of their enemy. General Dearborn was criticized for not having accomplished more with the resources at his disposal, as General Armstrong declared that he should have divided his attack and approached Fort George along the Queenston road, cutting off the route of retreat. This was actually Dearborn’s plan, but he failed to execute in time (Cruikshank, 1904, p34). Additionally, Dearborn managed in the next two weeks to incur two humiliating reverses on the Niagara Peninsula when American detachments surrendered, followed shortly by his resignation (Montross, 1958, p44).

Commodore Chauncey gained comfortable naval superiority on Lake Ontario when the Pike was launched. A few halfhearted engagements took place, but the Pike’s long guns never got the chance to inflict much damage (Montross, 1958, p44).

Significance

Although the Battle of Fort George did not play a major role in the outcome of the War of 1812, it would be a mistake to infer that the American cause did not benefit from this victory. Winfield Scott demonstrated that he could command a small army in battle, and was appointed brigadier in the regular army. He went on to lead the invading American army in the Mexican War and served as commanding general from 1821 until his death in 1828. Perry followed his naval victory by transporting his army across Lake Erie, where they became victorious in the Battle of the Thames. Unfortunately, this prodigious young man died of yellow fever just 5 years after the war (Montross, 1958, p44).

Primary Sources

- Palmer, T. H. (1814). The Historical register of the United States. Washington: Published by the editor T.H. Palmer.

- *Cruikshank (1902) references the Public Papers of Daniel D. Tompkins, Governor of New York (1807-1817) Vol. III. This source is available in print in the New York State Library, but an electronic version was not found.

- *Cruikshank (1902) also references the Powell Papers, Toronto Public Library. An electronic version could not be found.

Secondary Sources

- Cruikshank, E. A. (1904). The battle of Fort George. Welland [Ont.: Tribune Print.

- Cruikshank, E. A., & Lundy’s Lane Historical Society. (1902). The Documentary history of the campaign upon the Niagara frontier in the year 1813, part I (1813), January to June, 1813. Niagara Falls, Ont.?: The Society.

- Hurley, M. (2012, 05). Battle of fort george: Volleys over the niagara. Esprit De Corps, Canadian Military then & Now, 19, 40.

- Montross, L. (1958). Amphibious doubleheader. Marine Corps Gazette (Pre-1994), 42(4), 36-44.

For Further Reading

- Wikipedia: Battle of Fort George

- Canadian Encyclopedia: Battle of Fort George

- The History of Fort George