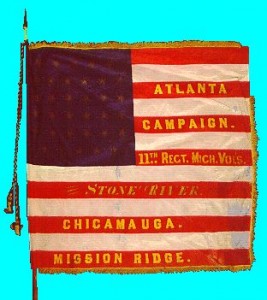

Bowman Park is a memorial park in Three Rivers, Michigan where it holds the location for a Colonial Sun Dial which was erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) for the memorial of Three Rivers’ first settlers. Which is also where Caroline Fellows Bowman Winn was buried. She was also the daughter of Colonel Abiel Fellows who fought in the American Revolution and was a Colonel in the War of 1812. Caroline was also the sister in law of one of Three Rivers founders John H Bowman. The Bowman park also holds a memorial dedicated to the men who served in the Michigan’s 11th infantry during the time of the Civil War.

The land where the current park is located was originally a cemetery for John H. Bowman’s family and early settlers in 1836. Years later in 1915 the Daughters of the American Revolution unveiled the Colonial Sundial and the certification that the lot would be a permanent memorial to John H. Bowman. The Civil War memorial statue “was erected by the citizens of Three Rivers Michigan in 1893 at the cost of $3,300.00. It stood at the intersection of M-60 and Main Street until it was moved to Bowman Park in 1928.”(e.g [4, p.89]). On the Civil War Statue is an inscription that read “Erected to the memory of our soldiers who fought for our union and liberty, 1861-1865. No nation ever had truer sons. In honor now, they rest. Their marches, sieges and battles in distance, duration, resolution, and brilliancy of results dim the luster of the world’s past military achievements.” (e.g [7, p.1]).

The Michigan 11th infantry was put together by William May who was a local business owner in White Pigeon, Michigan in the summer of 1861. They were originally called the St. Joe Regiment before officially becoming the Michigan 11th Infantry in September 16th. “The 11th Regiment, with its total enrollment of 1,323 men, left its White Pigeon post on Dec. 9, 1861. They shipped out by railroad from Sturgis, Michigan for Bardstown, Kentucky and remained there for basic training duty until March 1862.” (e.g. [6, p.1]). After training the men of the 11th guarded the Louisville to Nashville railroad line. While also going on marches to in pursuit of Confederate General John Hunt Morgan and his Morgan’s Raiders.

In November 1862, Michigan 11th infantry under the command of Colonel William L. Stoughton was assigned to 29th Brigade, 8th Division, Army of the Ohio. They participated in the advance on Murfreesboro, Tennessee from December 26th to the 30th. The volunteers were in some of the deadliest fighting at Stone River. The 11th was in the center of the Union line, which was heavily assaulted by the Confederates in such overwhelming numbers as to force it back toward Murfreesboro Pike.

James Wood Kings was a Civil War solider and newspaper editor who served in the Union army and was in the Michigan 11th infantry as a quartermaster sergeant. But he was also a reporter an editor of the Three Rivers Reporter. Through his detailed letters to his wife in Michigan. It gives an incite of the experiences James King went through as a solider. In a letter to his her, James describes the battle of Murfreesboro resulting skirmishing all throughout day.” The next morning at daylight, the battle commenced, by 9 o’clock the battle raged with fury all along the line”(e.g. [1, p.79]). The 11th was one of the first parties to cross Stone River, and was also among the troops that captured a Confederate battery. Through their fighting the Michigan 11th took on a casualty rate of 39%. A direct quote from King on the travesties he observed of the Civil War “Tis true that exposure and disease have carried away many of our soldiers, but the plains of Stone River have drank the blood of many of our bravest boys. Still there are enough of the 11th left to avenge their noble spirits, and with our gallant colonel to lead, we will wage a war of death and destruction to traitors wherever they may be found”(e.g. [1, p.78]). After the Union armies captured Murfreesboro, King depicts a vivid image of the aftermath of the resulting battle, “As I gazed over this field, I could see by the number of horses which lay on the ground where the most desperate carnage had been. Villages burned with fire and from warm ruins spread over the land. The groans of the wounded in the hospitals, and by the road side” (e.g. [1, p.80])

At the beginning of the New Year in 1863 the 11th was detached and placed on guard duty in Murfreesboro. The regiment also assisted in guarding rail lines and assisting in helping other regiments cross rivers. Until later being put back into full combat duty. Where the Michigan 11th participated in the Battle of Davis’s Cross Roads and Battle of Chickamauga.

Then in late November of 1863, James King and the Michigan 11th would participate in the Battle of Missionary Ridge which would be the defining moment in King’s military career because through his actions and bravery it earned him a nomination for the Medal of Honor. Before King’s involvement on November 23, 1863 he wrote to his wife Jenny about the heavy fighting as the Battle of Missionary Ridge was commencing. As he signed off to his wife little did he know that he would be the driving force that lead Union forces up the ridge. The next day November 24th, “King correctly anticipated the following day’s frontal assault against Missionary Ridge. He secured permission from Brigade Commander Colonel Stoughton to grab a rifle and join the ranks” (e.g. [1, p.116]) which was peculiar being that King was a quartermaster sergeant which had the duty of dealing supplies well behind the combat zone. Now in battle King moved with Stoughton’s troops the Michigan 11th. To engage the Confederate brigade of Otho F. Strahl at the base of the ridge. James King was observed by several of his comrades to charge ahead of the brigade. He became one of the first Union soldiers to enter the Confederate rifle pits. After battling in close quarter combat with enemy soldiers, the Union forces noticed they were vulnerable to enemy fire from further up the ridge and continued the climb uphill. Once again, the 11th observed King rush up the hill ahead of Stoughton forces. As Borden Hicks put it King “was one of the leaders through this storm of death and destruction,” (e.g. [1, p.118]). As the Union forces persisted on the Confederate artillery batteries King was hit in the right arm. Later on King described the scene from when he was shot. “A chestnut tree, about twenty inches in diameter, stood on the ridge where it began to slope to the east and lying beside it was a log nearly as large… Lying in this nook I would load lying on my back, then turn over and fire across the log at the Confederates who were working the guns. Every time I showed myself above the log Minie balls would whistle over me or strike the log at my right. I had loaded my gun lying on my back for the twenty-first time, and on rolling over to cock and cap it, I raised my right arm a little too high, a Minie ball struck it, breaking the bone just above the elbow joint.” (e.g. [1, p.118]). According to Eric Faust, King’s exploitation of the gap in the Rebel line had triggered the rout of Alexander P. Stewart’s entire division. Afterwards, James marched four miles back to the general hospital in Chattanooga where he would almost get his arm amputated but regimental surgeon William Elliott intervened and saved King’s right arm.

With the damage to his right arm James King was granted medical furlough and sent back to Michigan. Upon return King insisted that he be reinstated back into the Michigan 11th. In 1894 in the battles around Atlanta, King was injured when a Confederate shell exploded over head knocking him out and breaking his left shoulder. This wound would end King’s military career as he would spend the remaining time in Chattanooga until being official discharged on October 13th 1864.

Not until September 25, 1864 did the rest of the Michigan 11th return to Michigan. Through official records from A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion the regiment in total lost during service was “5 officers 107 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded and 2 officers and 194 enlisted to disease.”(e.g. [3, p.1286]) Through the long service that the men of the Michigan volunteer 11th infantry served in the Civil War. It may have not been one of the most famous regiments. But those men who served gives Southwest Michigan a sense of pride that in times of peril the men of the Michigan will come together for a greater cause.

Primary Sources

[1] Faust, Eric R. (2015). Conspicuous Gallantry: The Civil War and Reconstruction Letters of James W. King, 11th Michigan Volunteer Infantry The Kent State University Press

[2] Ross D.D Veterans Account of the Battle of Stones River The Natural Tribune

[3] Dyer , Fredrick H A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion 11th Michigan Infantry New York, Thomas Yoseloff, London

[4] Silliman House Library Three Rivers The Early Years Three Rivers Tribune

Secondary Sources

[5] Wilkinson, Gary.(2011) “History of Marvin S. Wood In the Michigan 11th Infantry Of the Civil War.” The Wood House http://oldwoodhouse.org/michigan-11th-infantry-cof-the-civil-war.com

[6] Bevard, Jermany. (2012) “History of the 11th Michigan Infantry.” All Michigan Civil War – 11th Michigan Infantry, www.allmichigancivilwar.com

[7] Faust, Eric R. (2015). The 11th Michigan Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War: A History and Roster Mcfarland

Further reading