Background

In 1793, John Graves Simcoe, the lieutenant-governor of the British providence of Upper Canada, ordered the construction of a fort along the western edge of Lake Ontario. At the time, war seemed almost inevitable with the United States as the British alliance themselves alongside Native Americans, who the Americans had been fighting. After tensions died down between the British and the United States in the 1790’s, they quickly rose back up in 1807. The fort was strengthen and ready for war by 1811, just in time for the War of 1812 to start. That fort became known as Fort York (9).

Fort York is located in what is now modern-day Toronto, along the western coast of Lake Ontario. During the War of 1812, it was considered a strong fortification that was strategically placed adjacent to the town of York. The town itself wasn’t very large, but still held strategic military significance due to the fact that the town was the host of the Parliament buildings for the providence of Upper Canada.

Before the Battle

Stepping back and looking at the entire scope of the war before the battle of Fort York, the United States had very few decisive victories and were essentially fighting a war that they had no plan for. The hope for the battle of Fort York was to change the tide for the United States, to get a decisive victory, and to actually prove to the British that they could survive as an independent nation.

Leading up to the battle, Commodore Isaac Chauncey was sent to Sackets Harbor, New York to create a fleet able to engage with British forces along Lake Ontario. The strategic belief was that a win along Lake Ontario could create an opportunity for an attack on Montreal, a surely devastating blow to the British forces. Chauncey was able to create a fleet of fourteen armed ships equipped with 112 guns, including 40 guns known as 32-pounders which were more powerful and had further range than the couple of 18-pounders at Fort York. The fleet also consisted of two smaller ships for transporting men as well (1). While Chauncey was preparing the fleet, Brigadier General Zebulon Pike, was in charge of readying troops for battle. General Pike was a renowned explorer of the lands that laid west of the United States and continued his service for the United States as a General in the War of 1812. By the time they were ready to sail, General Pike was able to assemble approximately 1700 men (5).

For this battle, Major General Henry Dearborn would be the top commander of all troops and the fleet. He would use Chauncey to assist him in commanding the fleet and Pike to assist him in commanding the troops. Originally, the target was going to be Fort Kingston, approximately 250 kilometers east of Fort York. After discussing and analyzing their options, Chauncey and Dearborn decided that they had too few men to take down the strong fortifications at Fort Kingston. However they did have enough to take the approximately 750 British regulars, a small Canadian militia, the Mississauga tribe, and the Ojibwa tribe (9) at Fort York and get a much needed victory for the United States.

The day before the fleet would set sail, Pike wrote a letter to his father from Sackets Harbor about the journey he was about to embark on. To his father he said, “If success attends my steps, honour and glory await my name — if defeat, still shall it be said we died like brave men, and conferred honour, even in death, on the American name” (3). He continued on and said that “if we are destined to fall, may my fall be like Wolfe’s — sleep in the arms of victory” (3).

On April 25th 1813, the fleet departed Sackets Harbor and set sail towards York. The fleet would later arrive the night of April 26th, allowing them to prepare a battle plan that would be carried out the following morning (8).

Meanwhile at the fort itself, the British troops and commanders had been hearing rumors throughout the winter months that the Americans were preparing for a siege upon the fort. The night the American fleet arrived, they were spotted by British troops stationed at the Highlands of Scarborough, approximately 8 miles outside the town. The troops quickly left to alert the fort and the town that an attack from the United States Navy was imminent. The bell in the church was rung, calling all able bodied men to prepare for battle (1).

The Battle

On the morning of April 27th 1813, the American forces were led by Dearborn, Pike, and Chauncey towards Fort York. The first wave of troops landed approximately 4 miles west of the town at about 8a.m. (8). That morning the winds were especially hard, blowing the boats off of their intended target. They ended up exposing themselves prematurely to the British forces who were led by Major-General Sir Roger Sheaffe (3). As the first group of soldiers stormed the shore, they were met with heavy fire by a small group of First Nation warriors who were in charge of defending the shoreline. They were outnumbered as well as out-maneuvered by the American troops and had no other option but to fall back into the woods. This initial attack was able to carve out a landing area on the beach, which allowed more room for American troops.

Back on the boat, Dearborn was a reluctant commander and put Pike in charge of leading the attack. Excited for battle, “General Pike, standing upon the deck, and seeing this pause of the first division, in an agony of anxiety exclaimed to the officers of his staff, ‘By — I can’t stay here any longer, come, jump into the boat;’ and setting the example, was quickly followed and rowed into the thickest of the battle” (3). Three companies of American troops then landed under Pike’s command, where they were met by British forces. In an attempt to drive the Americans back, the 8th Regiment of Foot charged the Americans with their bayonets drawn (7). The British were largely outnumbered and were forced to retreat after suffering heavy losses. Throughout the morning the American forces relentlessly pushed the British further and further back towards the fort. In a last ditch effort, Sheaffe then commanded his troops to rally around the Western Battery of the fort. The battery stood just west of the fort itself and was a strong fortification equipped with a handful of powerful cannons. If the British stood a chance in stopping the American advance, it would have to be at the Western Battery. This rally attempt was short-lived as the Americans troops continued their assault. With the help of American schooners bombarding the fort, it was only a matter of time until the British forces would have to give in. Sheaffe later ordered the British troops to retreat from the fort entirely.

As they retreated, Major-General Sheaffe ordered the naval stores and a ship that was under construction to be set ablaze to ensure the Americans would not be able to use the captured supplies. More importantly, the British set a fuse to the fort’s main gun powder magazine as they abandoned the fort. The explosion was enormously powerful, shooting stones and debris through the air. General Pike was left mortally wounded and the explosion alone killed 38 other Americans as well as wounding 222 more. The magazine exploded sooner than British had thought and accidentally killed and wounded 150 British soldiers and leaving 290 to be captured (5). As a severely wounded Pike was being carried off the field, one surgeon turned to him and said “The British union-jack is coming down, general — the stars are going up” (3). At the very least General Pike died knowing that he succeeded in what he set out to do that day. Pike was carried back to the fleet where he died by Dearborn’s side and with the British flag under his head. Just like he told his father, Pike died as he wished, “like Wolfe’s — sleep in the arms of victory” (1).

After the explosion, the remaining British troops fled to nearby Fort Kingston, the Mississauga and Ojibwa warriors fled into the woods, and the Canadian militia surrendered the town. The Americans did not make an attempt to further pursue the British forces any further as they had already surrendered the fort. By 2p.m. that day Fort York was considered a decisive victory for the United States (2).

After the Battle

After the battle, both sides were left with considerable casualties after just six hours of fighting. The Americans suffered a total of 55 killed and 265 wounded, the majority of the casualties coming from the explosion. The British on the other hand suffered a total of 82 killed and 112 wounded, as well as over 300 captured (7).

The next day, Dearborn and Chauncey came ashore to talk with British militia officials who had wished to surrender. After much deliberation, a surrender agreement was agreed upon. The terms that were agreed upon were that if the militia were to surrender, that all public stores and private property would remain unharmed. In the days following the battle, the militia of York surrendered the town as agreed upon. The American troops however, still burned and looted the town of York. The troops ended up raiding the public stores and burning several buildings, including the buildings of Parliament and shipyards outside of the fort.

By April 30th Dearborn had ordered his men to re-embark back to Sackets Harbor, but first ordering them to deliberately burn down other government and military buildings in the town that were previously missed. However, because of poor winds, the fleet was unable to leave until May 8th. To add insult to injury, the Americans would return to the unarmed Fort York in July 1813, to burn the barracks and a handful of other buildings that they did not burn at the time of the battle. The fort was held under American control until 1814 when the British returned and rebuilt the fort on top of the ruins from its previous battle. The Americans never made a second attempt at taking the fort during the remainder of the War of 1812, which was resolved by 1815.

Results of the Battle

All in all, the Battle of Fort York is considered to be a clear victory for the United States regardless of the casualties they experienced. Many consider the victory of Fort York to be important politically for the United States, as the months of military campaigning prior to April 27th were overwhelmingly ineffective. The Battle of Fort York was a much-needed boost in military and civilian morale (5). Although a political victory, strategically the battle did little to change the situation in Lake Ontario for the United States. Unfortunately for the United States, the battle did not create an opportunity for an attack on Montreal. It also cost them the talented commander, General Pike, in the process. Notably, the battle of Fort York marks one of the few times where Canadian civilians were attacked on their own soil.

The battle ended up being a strategic victory for the United States, as the town and fort were holding supplies that were intended to be transported for the war efforts in Lake Erie. Without the well needed reinforcements and supplies, the British were later defeated at the Battle of Lake Erie. In the end however, the British ended up getting the last laugh. The capture of Washington and the burning of the White House, Capitol, as well as other public buildings. This was easily seen as retaliation for what had happened at the Battle of Fort York (9).

Primary Sources:

1. Cumberland, Barlow. The Battle of York; an account of the eight hours’ battle from the Humber Bay to the old fort in defence of York on 27th April, 1813. Canada, 1813.

2. Salem Gazette Office. “Victory by Gen. Dearborn.” Received by Gen. P. B. Porter, 1 May 1813.

3. The Monthly Reporter. “Biographical Memoir of the late Brigadier-General Zebulon Montgomery Pike.” July, 1813. Pages 230-234.

4. Eddy, Oliver Tarbell. Death of General Pike at L. York. 1813, National Portrait Gallery.

Secondary Sources:

5. Thackorie, Indira (2013). “The Battle of York“. National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces.

6. Mills, Don (2013). “Battle of York“. National Post

7. Hickman, Kennedy (2017). “War of 1812: Battle of York“. Thought Co.

8. Roosevelt, Theodore. “Chapter 6: 1813 – On the Lakes.” The Naval War of 1812, vol. 9, Modern Library, 1882, pp. 267–289.

9. Benn, Calr. “A Brief History of Fort York.” History of Fort York

Further Readings:

10. Marketwired (2013). “Minister MacKay’s Statement on the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of York“. Ontario.

11. Cowan, James (2006). “Unearthed 1800s’ wharf hauled to Fort York“. National Post

12. Hood, Sarah (2008). “Tribute to tumultuous times; Fort York: Remembering a battle of a bygone era“. National Post

Pictures:

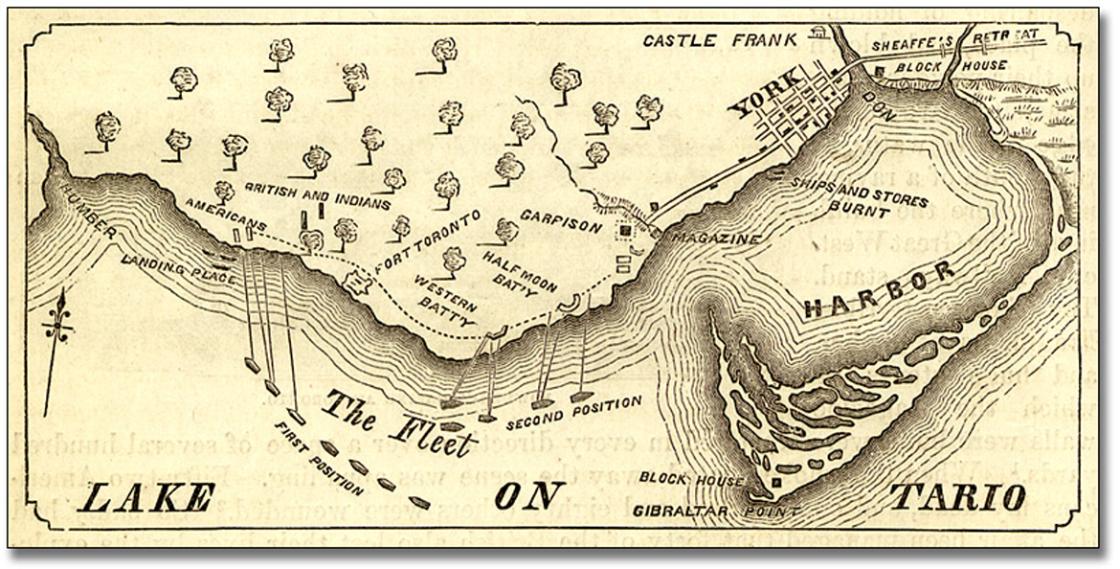

13. Map of the Battle of Fort York

14. Portrait of General Zebulon Pike

15. Letter from General Dearborn regarding the victory at the Battle of Fort York.