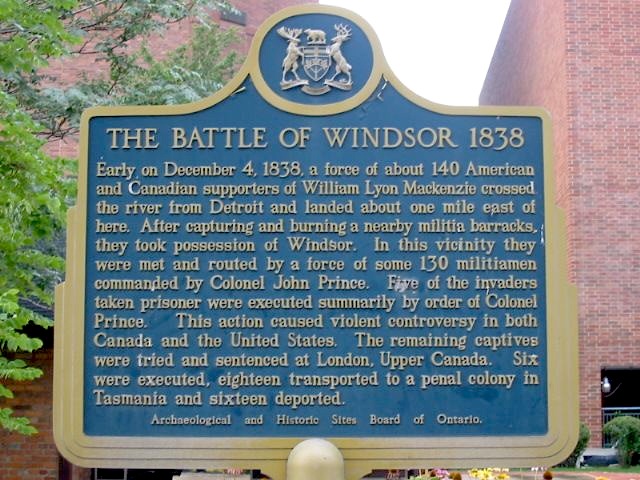

The Battle of Windsor is a story of the fall of the Hunter Patriots. It is the ending of a much larger story called the Patriot War, a year long conflict where the Hunter Patriots struggled to fight for Canadian Independence. It’s a story that is reminiscent to both the War of 1812 and the Revolutionary war, but at the same time it has stark differences from the two that all start with the Hunter Patriots themselves.

Hunter Patriots

The Hunter Patriots were a secret society that, drew their origins from Canada, where they were part of rebellions in both Upper and Lower Canada. These rebels were fed up with British rule in Canada and wanted Canada to become an independent nation, this was just after the War of 1812, anti-British sentiments were still prevalent in the population of both Canada and the U.S., but at the same time, Canada had defended itself from the U.S. in the War of 1812, thus the Patriots themselves still had anti-American views as well, this is evident in the fact the Hunter Patriots also denounced the United States government rather than rallying for another War of 1812, “Patriot meetings were being held in the leading cities and towns in the border states at which the United States Government was denounced as a tyranny, and no longer being worthy of popular support.” (6). These rebels became refugees in the United States with western New York, northern Ohio, and eastern Michigan becoming the centers of the Patriot movement. The Canadian refugees were welcomed with their tales of the woes of British oppression being met with open minds and sympathetic hearts. This American sympathy proved beneficial to the Patriots as food, clothing, money, ammo, and arms were sent to them as aid.

The Hunter Patriots themselves were a mix of people each with their own motives for joining the Patriot movement, “…there were, indeed, charlatans, rouges, and scoundrels among them, ready to promote their own selfish ends under the guise of furthering the cause of freedom, there were also the jobless poor, victims of the economic depression of these years and now in pursuit of any enterprise that promised notoriety or personal gain.” (6). There was indeed a reason for these people to engage in a conflict for Canadian independence and the Patriots had staged multiple events in order to achieve it.

Not many records of the Hunter Patriots exist due to a possible agreement among the leaders of the organization agreeing to wipe out all documents in the event that the rebellion failed,

“…in compliance to an agreement among the leading Hunters, all membership rolls and other records kept by the various lodges were to be burned in case the movement failed. This may well have occurred, since no trace of their records can be found, records which undoubtedly contained the names of many persons of wealth and position and no small number of ambitious politicians who would shield their identity with a once powerful brotherhood whose day had passed.” (6).

Rebellions and the Patriot War

Originally, the Patriots had staged rebellions in Upper Canada which had seen success, for example, their rebellion on Oct. 22, 1837 was a success. On Oct. 25, 1837, three days after this initial success, the rebels were met with a British regiment that quelled their forces, out manned and out armed the rebel forces were put down. The British had also staged an attack on St. Eustache, where they cannoned the building that the Patriots took cover in, out matched many patriots fled. Some of the Patriots had remained in a church for cover, the British set fire to the church, and if the Patriots attempted to escape burning to death they’d be met with bayonets and gun fire. It was gruesome,

“…between the sleepers were scattered the remains of human beings injured in various degrees—some with merely the clothes burned off, leaving the naked body, while here and there the blackened ribs were all that the fierce flames had spared. Not only inside of the Church but without its walls, was the same revolting spectacle, and farther off were bodies, still unscathed by fire, but frozen hard by the severity of the weather.” (4).

The rebels in lower Canada which had heard of this gruesome punishment had laid down their arms and fled to the border stated of the U.S., where they culminated (4).

Another example of Hunter Patriot action was the capture of the Schooner Anne, it was among the most important and prominent events staged by the Hunter Patriots. The Schooner Anne’s capture happened about a year prior to the events at Windsor, and it shares a lot of similarities to the battle. The Schooner Anne was capture on Jan. 8, 1838, twenty miles away below Detroit in the United States, along with weapons the Hunter Patriots had stolen, they also took two scows, two divers boats, a large schooner, three field pieces, two twelve pounders, and one six pounder (1).

In response to the capture of the Anne, the Canadians sent 220 militiamen to seize the Anne and put an end to its terror, while the United States dispatched the Erie and Brady with another 220 armed militiamen to also seize the Anne (1). The United States did not aid the Hunter Patriots due to them wanting to preserve neutrality between the nations.

“On the day the Anne left Detroit, a public meeting was held in the city hall, which was addressed by George C. Bates, Theodore Romeyn, Attorney General Pritchette, Danial Goodwin, and Maj. Jonathan Kearsley, in which the meeting resolved to sustain the government in its efforts to preserve neutrality.” (4).

Unlike the Canadian militia, the United States militia came back the same night after their departure due to not discovering the Patriots along the American shore (1). It was reported that the Patriots had captured Whitewood Island, owned by the British. The Patriots aboard the Anne fired upon the city of Malden, in which the British troops returned fire. Canadians in the United States that sympathized with the Patriots rallied with excitement in hopes of aiding the Patriots and their efforts, a group of men in support of the Patriots attempted to seize the American steamboat Brady, but this was quelled by the civil authorities (1).

The Canadian militia gave chase to the Anne. Troops leaving the Lime Kilns were ordered to watch the schooner at Elliott’s Point by Col. Radcliff. Gen. Sutherland and 300 militiamen departed from Hickory island and set up position at Bois Blanc island. When the Anne attempted to make its way past Bois Blanc, it was met with the fire of militiamen that had taken cover behind trees. The Anne crashed onto the beach and the militiamen made their way onto the ship, where the rebels put up no resistance and surrendered. The Patriots were then taken as prisoners. (4)

The Hunter Patriots had attempted to take multiple islands in hopes of gaining a foothold that would allow them to launch an attack on the Canadian mainland rather than an attack on the Canadian borders like with the Anne. These were in the form of an attempt to seize Fighting island and the Battle of Pelee island. These both had failed with the British and Canadian troops overwhelming the Patriots and forcing them to flee. After these attempts staged by the Patriots, both the United States and British governments became much more watchful of their potential actions. With the fear of spies being sent to infiltrate the Patriot ranks, they became even more secretive with their plans and were much more cautious, leading to their secret organization known as the Hunters’ Lodges. Between the time of the failures to gain a foothold on attacking the Canadian mainland and the Battle of Windsor, the Hunter Patriots were much quieter (6).

The Battle of Windsor

The Hunter Patriots had formed a plot to take Windsor on Jul. 4, 1838. The plot was originally created by a man named Henry S. Handy, who called for the organization of twenty thousand revolutionaries to be mobilized by horse. The plan was to start the revolution of upper Canada by capturing Windsor with weapons they would obtain by raiding both the armories of Dearborn and Detroit. After capturing Windsor, the Patriots would then spread their supporters and members throughout Canada where they were to secure weapons and fortify key locations. This original plan failed when, “forty ruffians crossed over into Canada and raided the town of Sarnia.” (6), this led to the Detroit guards of the weapons arsenal changing and the scheduled raid failing. The Patriots attempted to gather arms from another group of Patriots in Cleveland, who had plans of their own so they didn’t provide them arms. The first attempt to seize Windsor may have failed, but this wasn’t their final attempt.

Five months after the initial attempt to take Windsor had failed, a second attempt was staged on Dec. 4, 1838. This attack was being planned as early as November where a large number of Patriots were culminating and planning to invade Windsor,

“From about the first of November it was reported, and generally believed, that large bodies of Brigands, from all parts of the United States, were wending their way to the State of Michigan for the purpose of invading our country.” (2).

With this knowledge, the militiamen remained vigilant and ready for a sudden attack staged by the patriots. They had pinpointed areas of potential attack by the Patriots, which were Malden, Sandwich, and Windsor. In Sandwich’s case, the citizens participated in night patrols. Col. Prince at Windsor was supposed to request two companies from Malden, but he refused, “Col. Prince declined complying with, intimating something like fear that such an application would be considered as an evidence of cowardice.” (2), Prince assured the people that his battalion would be enough to quell the rebellion, but the people doubted this notion. Col. Prince’s men in charge of Windsor were noted as being slovenly and unqualified to defend Windsor, and they were the prime target for a surprise attack. Capt. Lewis, entrusted with Windsor, was noted as being negligent with his duties (2).

On Nov. 30, 1838, between 400 and 600 Hunter Patriots were reported to have been seen having set up camp on a farm, which was located 3 miles south of Detroit. On Dec.1, 1838, they had been reported having left the camp. They had spread themselves among taverns in Detroit. It was also reported that the sub-treasurer of the Patriots had taken their funds and fled. On Dec. 3, 1838, it was believed that the Hunter Patriots had given up their goal and left, but this deceived the people of the volunteer patrols who had let their guards down that night (2).

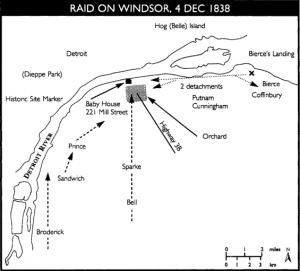

“In charge of the Patriots was a Lucius V. Bierce, who had anticipated gathering 400 more followers in Detroit. In command of his 3 divisions were S.S. Coffinbury, Cornelius Cunningham, and William Putnam. A Gen. Hugh Brady oversaw preventing border crossings to Canada but had done an unsatisfactory job in doing so. On Dec. 3, 1838, Bierce had captured the American steamship Champlain and crossed the Detroit river. With about 300 men he crossed and landed at a farm north of Windsor. The Patriots marched on Windsor, with a Sgt. Fredrick Walsh in command of a small detachment of men he defended against the attack, where he expended all his ammo and attempted a retreat.” (5)

The Patriots pushed onwards and captured a barracks, where they secured weapons and then set fire to the building. The fire also reached a house that also burned down. They also Captured an African American man named Mills, who refused to join the Patriots and was shot for his refusal. The Patriots then continued to set fire to the steamship, Thames. After receiving the alarm of an invasion, militiamen at Sandwich responded by sending about 40 men to retaliate, these men were then absorbed by Col. Princes group of 60 men. A Capt. Lewis was among the people fleeing Windsor where he explained the burning of the barracks and his defeat at the hand of the Patriots. A Capt. Thebo chose to circle around to the rear of Windsor which had given the militia an advantage by cutting off the escape of fleeing Patriots. The others marched through Windsor. With information that the Patriots were fleeing, the militia gave chase and fired at the Patriots. The Patriots had tried to flee for the woods but were met with Capt. Thebo and his men who had trapped the Patriots and subsequently quelled their rebellion. “On the morning of Dec. 4, 1838, large numbers of Patriot reinforcements were lined up along the Detroit river, with enough to overwhelm the Canadian forces in the vicinity of Windsor. But the confusion reigned among the in-coming recruits and the authorities as well as the Detroit river being patrolled by American vessels.” (6). It is likely that if reinforcements had arrived to assist at Windsor, the Patriots would have succeeded, but with the confusion and American authorities quelling the Patriots, a potential victory was lost.

Aftermath

The following day, Dec. 5, 1838, the Patriots paraded through the streets fully armed, but leading Hunters disbanded them. After their subsequent dismissal, Bierce stepped down from his command of the Hunter Patriots and instead continued down a different path. When brought to court for his participation with the Hunter Patriots, the jury failed to indict him, and he was a free man. He had been elected mayor later in life and was appointed by Lincoln as an adjutant general in the Union. Wealthier and more influential men like Bierce were lucky and able to escape punishment for their participation with the Patriots, they were able to secure positions of power where some continued to push their anti-British views.

Others were not as lucky as Bierce, in fact some of the Patriots were executed, others were either deported or jailed. One such case is Samuel Snow’s, who was exiled for participating with the Patriots. Snow was at the Battle of Windsor and was captured after attempting to flee into the woods. “Fourteen of us were now escorted up to London.” (3). He was tried along with his fellow rebels at London in front of the crown. Three of his fellow men pleaded insanity, and two had succeeded in their plea. Among those found guilty, a few were picked to be publicly hanged, those men were Hiram B. Lynn from Michigan; Daniel D. Bedford, Colonel Cunningham and Gilman G. Doane from Canada; and Albert Clarke and Amos Perley from Ohio. The prisoners were then taken to Toronto and then Fort Henry, from Fort Henry they were taken somewhere without knowing where they were going, a Asa Puest died on the journey by ship, “…was relieved of future sufferings by death.” (3). They finally reached the island where they were exiled, Van Dieman’s Land, they had spent years exiled from home leaving behind wives and children.

After the Battle of Windsor, attempts to start a revolution in Canada seized, with a few smaller attempts occurring but not on the scale of the ones before them, most of these smaller plans failed to even reach execution. The Hunters’ Lodges were denounced for the people believed that Canada itself should choose who rules it rather than a small group of revolutionaries determining the fate of the nation. The Hunter Patriots became a skeleton of their former selves, being held together only by anti-British sentiments, overtime these sentiments faded and when Canada was granted the ability to self govern the Hunter Patriots faded from existence.

Primary Sources:

- The Battle of Windsor (1838). Library of the Public Archives of Canada

- The Michigan Frontier (1838). Newbern Spectator. New Bern, North Carolina.

- Snow, Samuel (1846). The exile’s return, or, Narrative of Samuel Snow, who was banished to Van Dieman’s Land for participating in the Patriot War in Upper Canada in 1838. Cleveland, Ohio.

Secondary Sources:

- Ross, Robert B. (1890). The Patriot War. Detroit Evening News, Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society.

- Fryer, Mary B. (1996). More Battlefields of Canada. Dundurn, Saskatchewan.

- Kinchen, Oscar A. (1956). The Rise and Fall of the Patriot Hunters. Bookman Associates, New York

- Tiffany, Orrin E. (1905). The relation of the United States to the Canadian rebellion of 1837–1838. Buffalo Historical Society.

More Readings: